24 HOURS CENTENARY – MAKES, MARQUES and IMPRINTS ⎮ Talbot figured among top contenders during the 1930s and 1950s, with two drivers closely associated with the constructor's history at the race: Louis Rosier, who secured Talbot's sole win in 1950 at the wheel of a car adapted from a Grand Prix single-seater, and Pierre Levegh.

Here's a quick rundown on the marque's multiple changes of ownership. British in origin, Talbot was initially associated with the English branch of French company Darracq, then bought by Anthony Lago in 1932. In 1958, Talbot was taken over by Simca who, integrated into Chrysler Europe, resold the constructor to Peugeot in 1978. Now it belongs to PSA which has become Stellantis.

From Talbot to Talbot-Lago

Talbot took its rookie start in the 24 Hours with two cars in 1925, then went on to claim the third step on the podium three years in a row in 1930, 1931 and 1932. The cars have been seen regularly at the Le Mans Classic since its creation in 2002, easily recognisable by their apple green color and huge additional central headlight.

The marque's standout model after its takeover by Anthony Lago around 1935 was the T150 C available in very limited series, the Lago Spéciale and Lago Supersport (SS). The latter inspired the great French body-makers of the 1930s at a time when their talent dominated automobile styling. One Talbot took the start in the 1935 24 Hours, two did so in 1937, three in 1938 and four in 1939.

After World War II, Talbot developed a favourable reputation in many European Grand Prix thanks to T26 C. Three competed at Le Mans in 1949, three again in 1950, six in 1951, four in 1952, three in 1954, two in 1956 and one in 1957.

1950 | Louis Rosier's marathon win

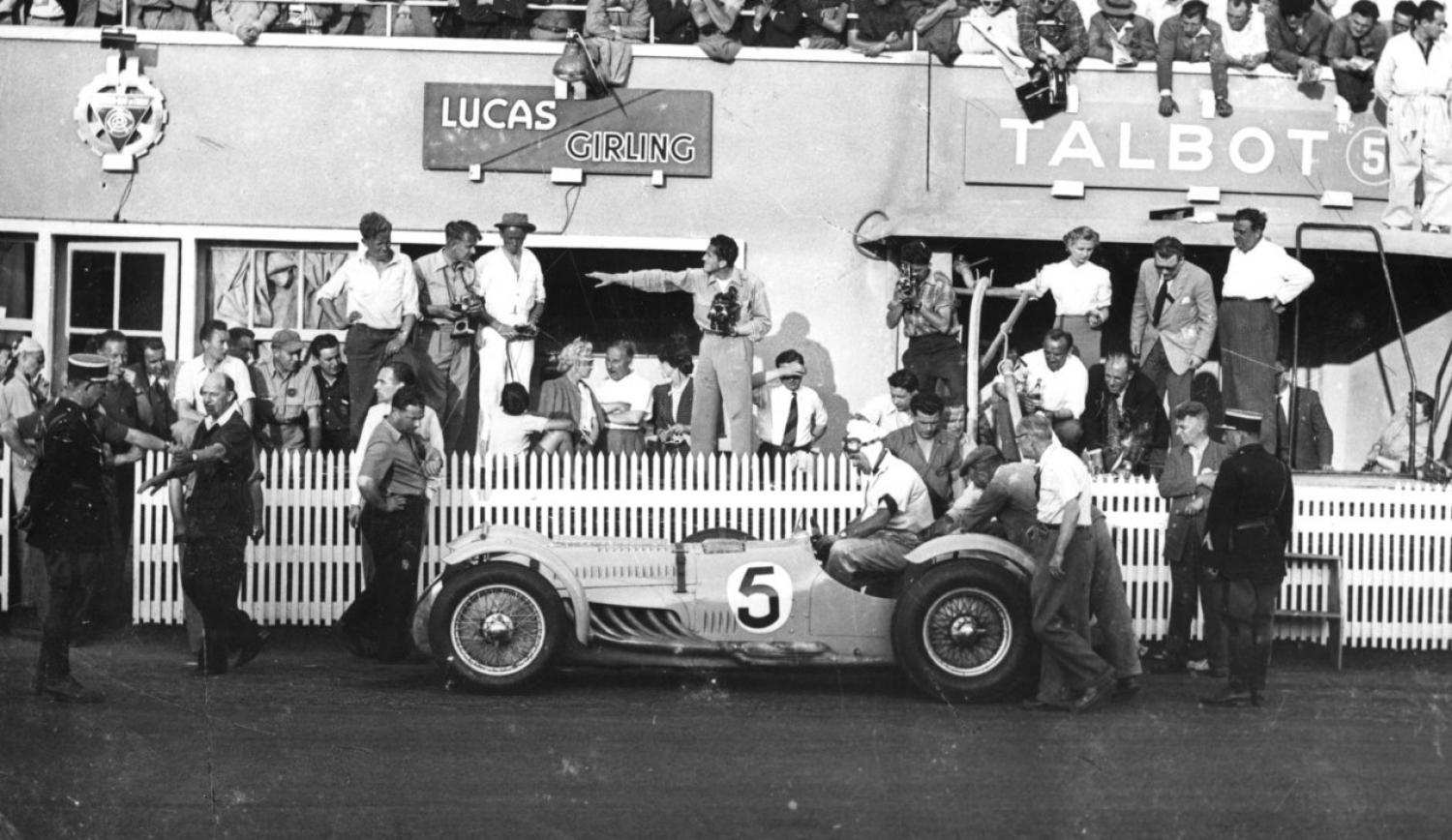

The 1950 24 Hours was a watershed moment for Talbot. Along with his son Louis, Jr. (known as Jean-Louis), French driver Louis Rosier won the race after a staggering 23-hour stint in his T26 GS during which a night owl smashed the car's windscreen, injuring Rosier's eye. He also had to replace the car's rocker arm ramp damaged after a failed gear change at Mulsanne, calling upon his loyal mechanic and former Bugatti employee Robert Aumaitre (who later became a technical steward at the 24 Hours). Rosier, Jr. only took the track for a few laps, a decision he has always defended.

The Talbot winner in 1950 is one of those old Grand Prix cars known as "offbeat single-seaters" to which were added motorcycle-style fenders and headlights. Enveloping bodywork became the fashion.

1952 | Victory falls through Pierre Levegh's fingers

In 1952, also at the wheel of a powerful T26 GS, Pierre Levegh achieved an equally stunning 22-hour showing. While in the lead with a five-lap advance on Mercedes, his engine failed just one hour from the chequered flag.

Duly impressed by the French driver's performance, German team owner Alfred Neubauer recruited Levegh to join forces with Juan Manuel Fangio and Stirling Moss among others for the 1955 24 Hours. But, what should have been amounted to a career highlight turned into the most catastrophic disaster in motorsport history when a crash sent a large piece of debris into a crowd of spectators, killing 83, as well as Levegh himself.

After Rosier, Sr.'s win, Talbot's best results at the 24 Hours are credited to Pierre Meyrat/Guy Mairesse and Pierre Levegh/René Marchand, second and fourth, respectively, in 1951. Rosier, Sr. took the start six times between 1938 and 1956 at the wheel of a Talbot, namely with teammates Fangio in 1951 and Jean Behra in 1956.

PHOTOS (Copyright - ACO/Archives): LE MANS (SARTHE, FRANCE), CIRCUIT DES 24 HEURES, 1930-1952 24 HOURS OF LE MANS. From top to bottom: Louis Rosier, Sr. and Jr.'s #5 Talbot in its box in 1950; the #15 Talbot of Brian Lewis/Hugh Eaton claimed the marque's first podium 20 years earlier; in 1938, French duo Jean Prenant/André Morel (#5) achieved the same result with the T150 Super Sport; the Talbot shared by Rosier, Sr. (at the wheel) and Jr. after the finish in 1950 (notice major damage to the windscreen caused by impact with a night owl); two years later, Pierre Levegh (#8) spent more than 20 hours at the wheel, and was forced to retire while in the lead.